Of Biblical Proportions

April 5, 2024

In the center of a Masonic Lodge is the altar of obligation upon which rests the Volume of Sacred Law, the Great Light in Masonry. In the Grand Lodge, Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Minnesota, the VSL is the Holy Bible; specifically, the Authorized, also known as “King James” version.

Why is that? First, it’s Tradition to use the King James Bible (KJB) in Lodges. A second, and more modern-day reason, in my opinion, is more pragmatic: the text is not subject to copyright!

Due to the beauty of its prose, the KJB has been an unparalled linguistic influence on the English language. You may be surprised to learn that many words and phrases we use today originated in this text. The “writing on the wall” comes from Daniel 5; “the powers that be”, Romans 13; “scapegoat”, Leviticus 16; “fly in the ointment” and “vanity of vanities”, Ecclesiastes/Kohelet; “sign of the times”, Matthew 16…these are just a few examples of how the KJB has entered our lexicon.

Who was this James?

James Charles Stuart (1566–1625) was King James VI of Scotland from 1567, as well as James I of England and Ireland beginning in 1603. Son of Mary, Queen of Scots, he succeeded her on the throne following her abdication. Only 13 months old at the time, his reign in Scotland and governance was overseen by a series of regents, becoming ruler outright when he was age 13. As James VI and I, he was ruler of a personal union of the Scottish and English crowns.

Some context may be helpful to underscore the importance of the KJB. In 1500s England, there were several versions of Bibles in use. The Great Bible (1539) was the first English translation legally authorized for use in the Anglican Church, by King Henry VIII. Produced by English Puritans in exile, the Geneva Bible (1557-60) had copious Calvinist and Puritan notes in the margins (and so, was objectionable to the English monarchy). It holds the distinction of being the first Bible translated from Aramaic, Greek, and Hebrew. The Bishop’s Bible (1568) was a Church of England document created as an attempt to replace the Protestant-leaning Geneva translation. With the variety of biblical texts, you can imagine all the confusion and dissension as to what was the “correct” Bible.

An ulterior motive

The “King James” version was essentially a political statement document, intended to settle disagreements over reforms in and pressures to the Church of England. James believed in the divine right of kings…a theological basis for monarchy, if you will. He so thoroughly disliked the Geneva Bible and its additional notes that disparaged royals and ecclesiastical hierarchy that he commissioned an Authorized (by him, as king) version, which would remove the marginal notes and thereby quash printed criticism.

Fortunately for us, James chose to compose a scholarly work. He appointed six committees (a total of approximately 50 people) to prepare the new translation. Work began in 1604, finishing in 1611. The scholars drew upon previous versions (Tyndale and Geneva, especially), working from Greek, Aramaic, Hebrew, and Latin. Today’s English Standard and English Revised versions, the Revised Standard Version, and the New Revised Standard Version are just a few examples of modernized-language derivatives from the KJV, for instance.

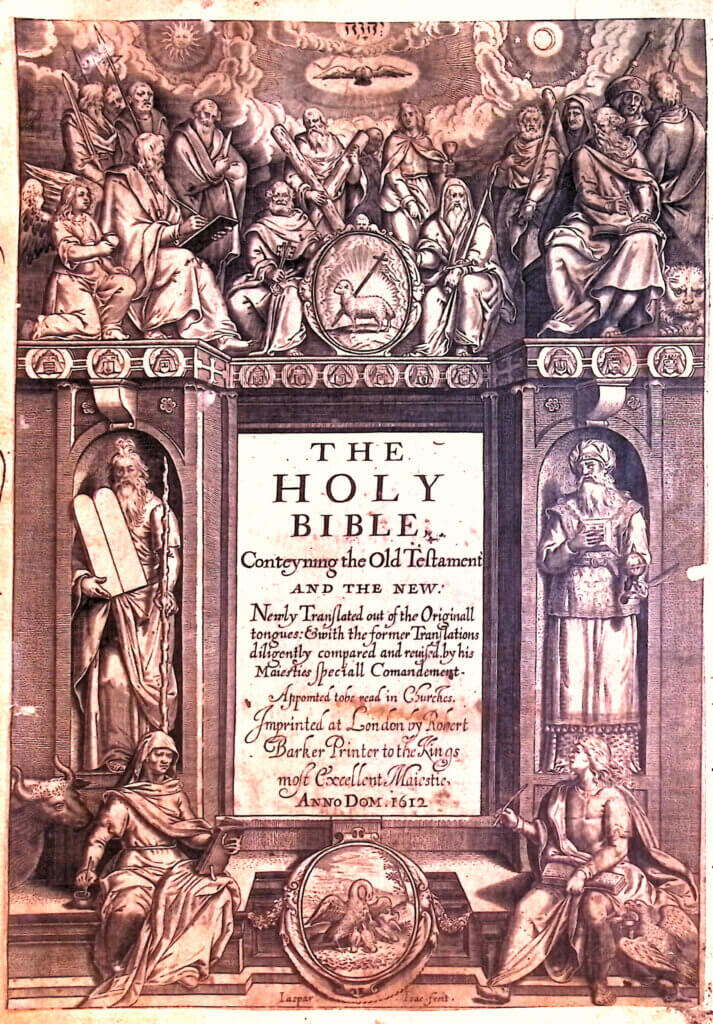

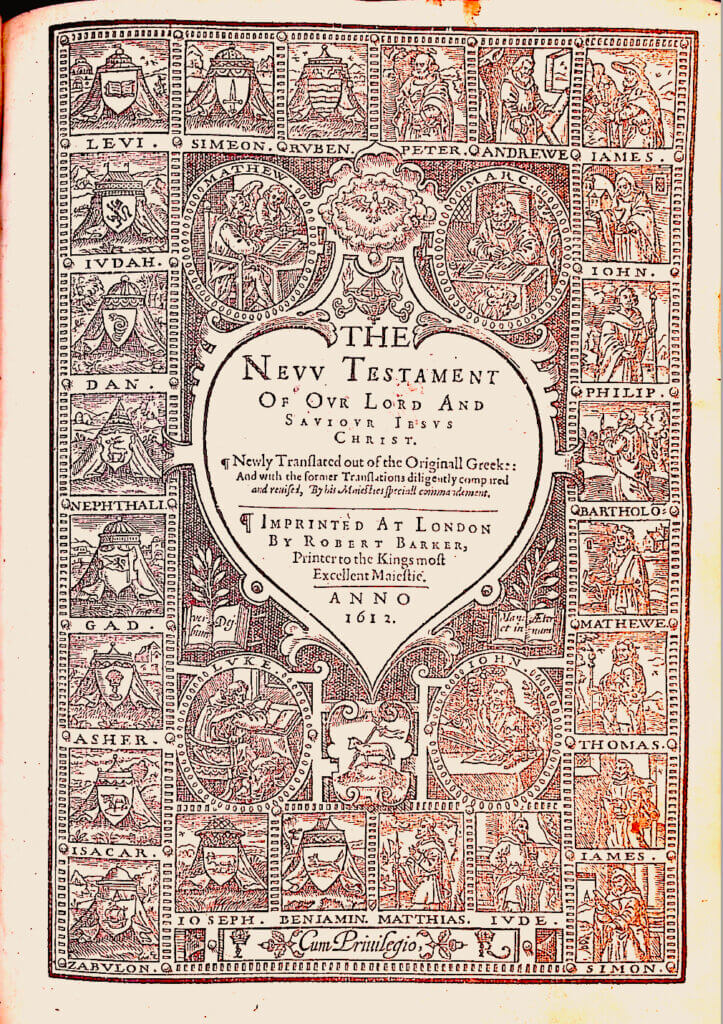

Recently, a copy of the KJB was rediscovered in the Nelson Library collection. While that fact may not strike you as earth-shattering, this find is of great consequence. The original printing / publication of the KJB was in 1611. Our copy is from 1612.

Let that sink in a moment. As of this writing (2024), that was 412 years ago. For historical perspective: that’s just five years after the first permanent English settlement in North America (Jamestown Virginia, 1607), and eight years before settlers came to Plymouth (Massachusetts) in 1620. This Holy Bible is definitively the oldest volume of any kind in our library. If you hadn’t already guessed, it is extremely rare.

Hallmarks

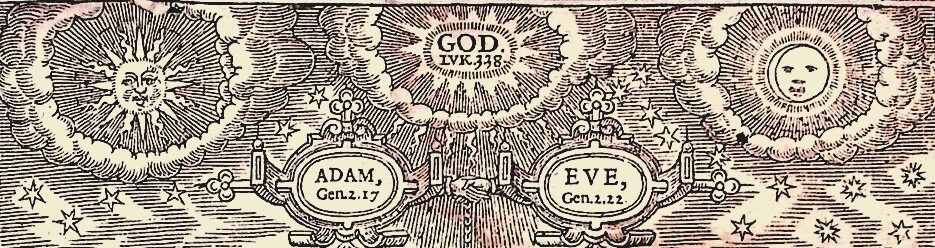

This KJB has unique identifiers. Published by Robert Barker (the King’s Printer), it is the first printing in Quarto size, and with Roman type. By Quarto, it means that the sheet of paper was folded in half twice to make four leaves or eight individual pages. Accordingly, when a volume is printed in Quarto size it is much more portable, and may be carried around more easily than the full-scale Folio size meant for church pulpits. This book’s dimensions are 23 cm. high x 18 cm. wide x 8 cm. deep/thick. This First Quarto Edition is classified an H313, according to the A.S. Herbert Historical catalogue of printed editions of the English Bible, 1525-1961.

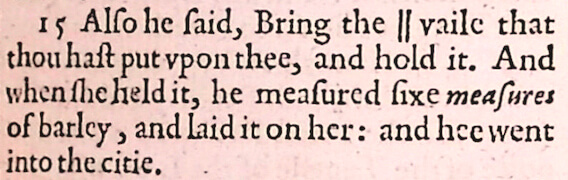

The aforementioned work, also known as the “He” Bible, is an anomaly. There were an estimated 351 errors carried over from the first printing in 1611, into this one of 1612. The most notable inaccuracy in this variant, Ruth 3:15 reads: Also he said, Bring the vaile that thou hast put vpon thee, and hold it. And when she held it, he measured sixe measures of barley, and laid it on her: and hee went into the citie. Note that the last phrase states “hee”; according to the Jewish Publication Society, the accepted translation is “she”.

How did we get this item?

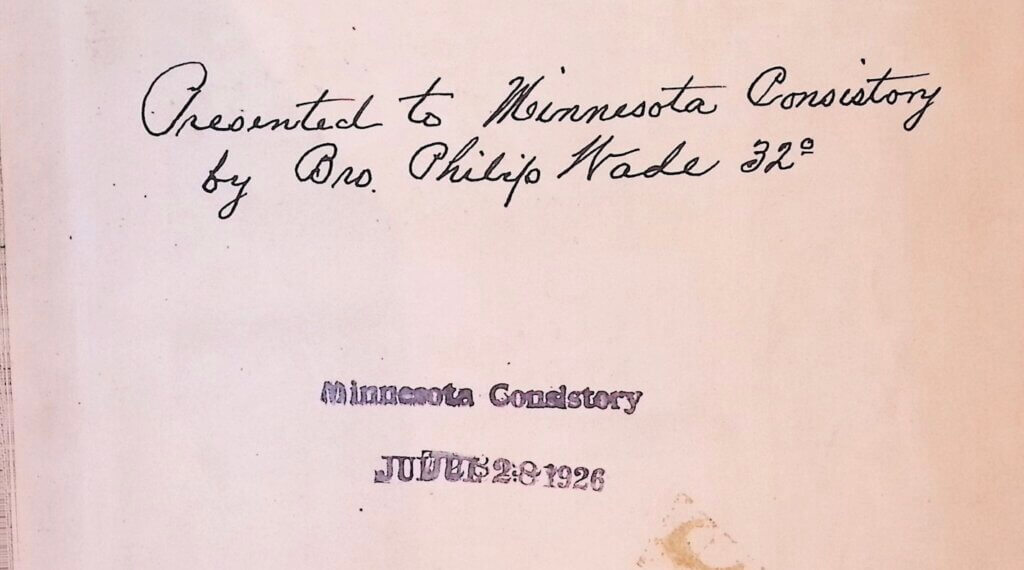

Unfortunately, we don’t know much about the long-departed donor of this treasure. He inscribed his name on a flyleaf page, thus: Presented to Minnesota Consistory by Bro. Philip Wade, 32˚. Beneath the inscription, is a date stamp: July 28 1926. There are two Phillip [sic] Wades in the Grand Lodge archives, both were members of Ancient Landmark Lodge No. 5, Saint Paul. They joined in 1915 and 1918, respectively. Both Philip Wades were born in England. They were probably father and son, and at least one of them belonged to the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, Saint Paul Valley (formerly Minnesota Consistory). Brother Wade’s connection to England helps make sense as to why we have this English book.

Enter 21st Century technology

Because of the fragility of this volume, it will rarely, if ever, be on display. This is where a “new-to-us” tool we’re testing helps us show this Bible to the public. The images of the 1612 Bible were produced by a CZUR (pronounced see-zur) ET24 Pro overhead scanner, on loan from Grand Lodge.

As you can see from the images, the clarity is remarkable. Surprisingly, each page takes only about 1.5 seconds to scan. The unit’s software automatically corrects for curvature of the open book pages, so the end result is a flat, legible likeness. Additionally, you may save the scanned images into a searchable pdf, thanks to the software’s optical character recognition. The CZUR scanner is a game-changer, giving the public a way to view items which would otherwise never be seen.

Special thanks to: W.B. Joel Friedman of Cataract Lodge No. 2 for his assistance with the Hebrew text; Erika Giddens of the Folger Shakespeare Library, and Karis Blaker of the Styberg Library of Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary for their assistance with identifying the “Wade” King James Bible. An exhaustive historical study of the Authorized Version may be read in A Textual History of The King James Bible, by David Norton.

Fiat Lux,

Mark A. Anderson, KYCH, OPC, 33º